Every year, over 1,000 generic drugs get approved by the FDA. That’s more than 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. But how does a generic pill go from a lab to your pharmacy shelf? It’s not a shortcut. It’s a precise, tightly regulated process called the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). And if you think it’s just copying a brand-name drug, you’re missing the real science behind it.

What Is the ANDA Process?

The ANDA is the legal pathway the FDA uses to approve generic drugs. It was created by the Hatch-Waxman Act in 1984. Before that, generic companies had to repeat every single clinical trial the original drug maker did-costing hundreds of millions and taking over a decade. Hatch-Waxman changed that. It said: if you can prove your drug is the same as the brand-name version, you don’t need to redo the safety studies. That’s the "abbreviated" part.

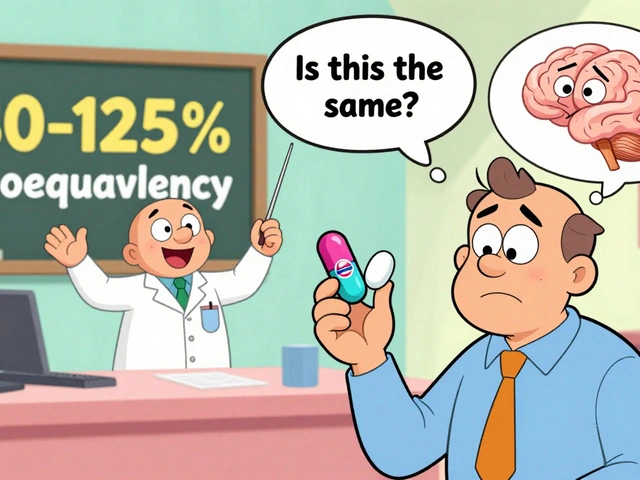

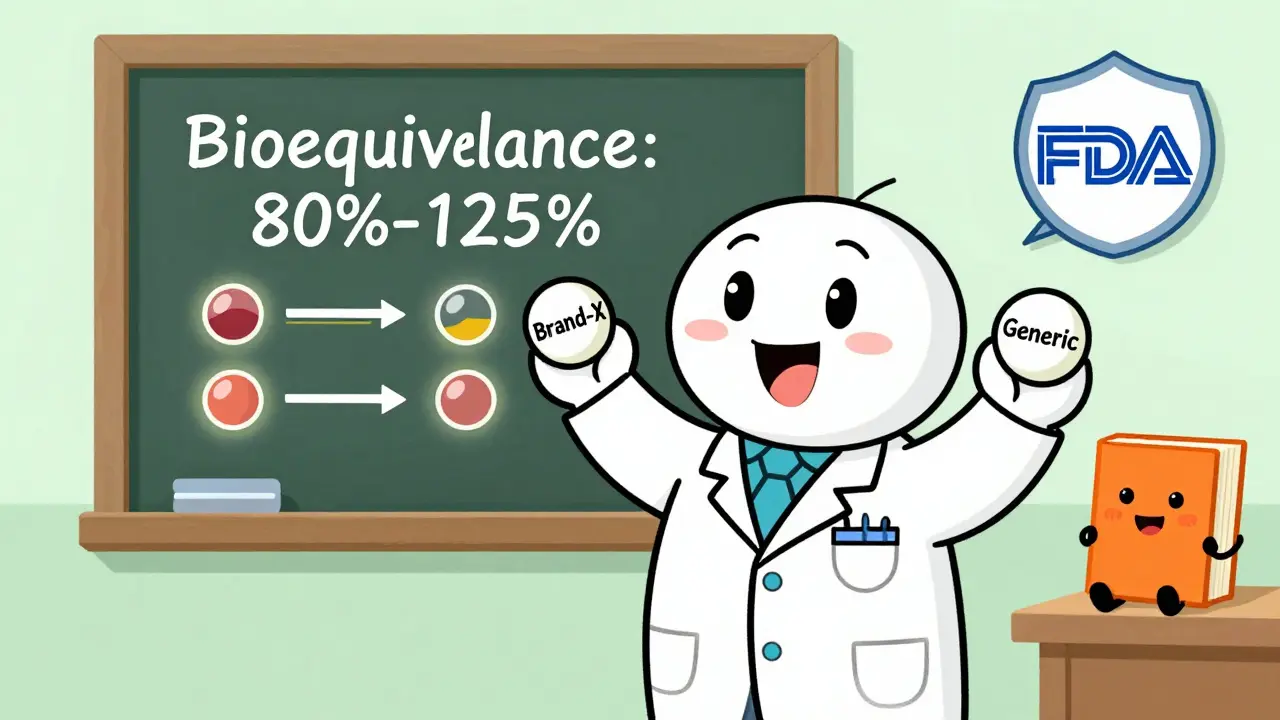

But "abbreviated" doesn’t mean easy. The FDA still requires proof that your generic is identical in every way that matters: same active ingredient, same strength, same form (tablet, injection, capsule), and same way it gets into your body. The real test? Bioequivalence. Your drug must deliver the exact same amount of medicine into the bloodstream at the same speed as the brand-name version. Not close. Not almost. Exactly.

Step 1: Choose the Right Reference Listed Drug (RLD)

Before you start testing, you need to pick the right brand-name drug to copy. That’s called the Reference Listed Drug, or RLD. It’s listed in the FDA’s Orange Book-a public database of all approved drugs and their therapeutic equivalence ratings.

You can’t just pick any version. The RLD must be the one the FDA considers the standard. If the original drug has multiple formulations (like immediate-release and extended-release), you have to match the exact one you’re copying. If the RLD is discontinued or pulled from the market, you can’t use it. You’ll have to find an alternative RLD approved by the FDA, or your application gets rejected before it even starts.

Step 2: Prove Pharmaceutical Equivalence

This is where you show the FDA your drug is chemically identical to the RLD. You must prove:

- The active ingredient is the same compound, in the same amount

- The dosage form is identical (e.g., 500mg tablet, not capsule)

- The route of administration is the same (oral, topical, injectable)

- The conditions of use match (same indications, same patient population)

Inactive ingredients (fillers, dyes, preservatives) can be different-but they must be safe and not affect how the drug works. If your tablet uses a different binder than the brand, you need data to prove it doesn’t change absorption. The FDA checks this in Module 3 of your ANDA submission, which includes detailed chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) data.

Step 3: Conduct Bioequivalence Studies

This is the make-or-break step. Bioequivalence means your drug behaves the same way in the body as the brand-name drug. The FDA requires a clinical study with 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. They take your generic and the RLD on separate occasions, and blood samples are taken over several hours to measure how much drug enters the bloodstream and how fast.

The results must fall within strict limits: the average amount of drug absorbed (AUC) and the peak concentration (Cmax) must be within 80% to 125% of the RLD’s values. That’s not a suggestion-it’s a hard rule under 21 CFR Part 320. If your numbers are outside that range, the FDA will reject your application.

For complex drugs-like inhalers, creams, or injectables-bioequivalence is harder to prove. The FDA has special guidance for these. A nasal spray, for example, might need imaging studies or in vitro testing to show it delivers the same dose to the right part of the nose. These applications take longer and often get more questions from reviewers.

Step 4: Prepare the ANDA Submission

Your application must follow the electronic Common Technical Document (eCTD) format. It’s a standardized structure with five modules:

- Module 1: Administrative info (company details, fees, certifications)

- Module 2: Summaries (overview of CMC, bioequivalence, labeling)

- Module 3: Quality data (how you make the drug, purity, stability, manufacturing controls)

- Module 4: Nonclinical and clinical data (bioequivalence study reports)

- Module 5: Labeling (must match the RLD exactly, except for minor differences in inactive ingredients)

Everything must be in the right place, labeled correctly, and formatted to FDA specs. A single misplaced table or incorrect file name can delay your review. Most companies hire specialized regulatory consultants just to get this right.

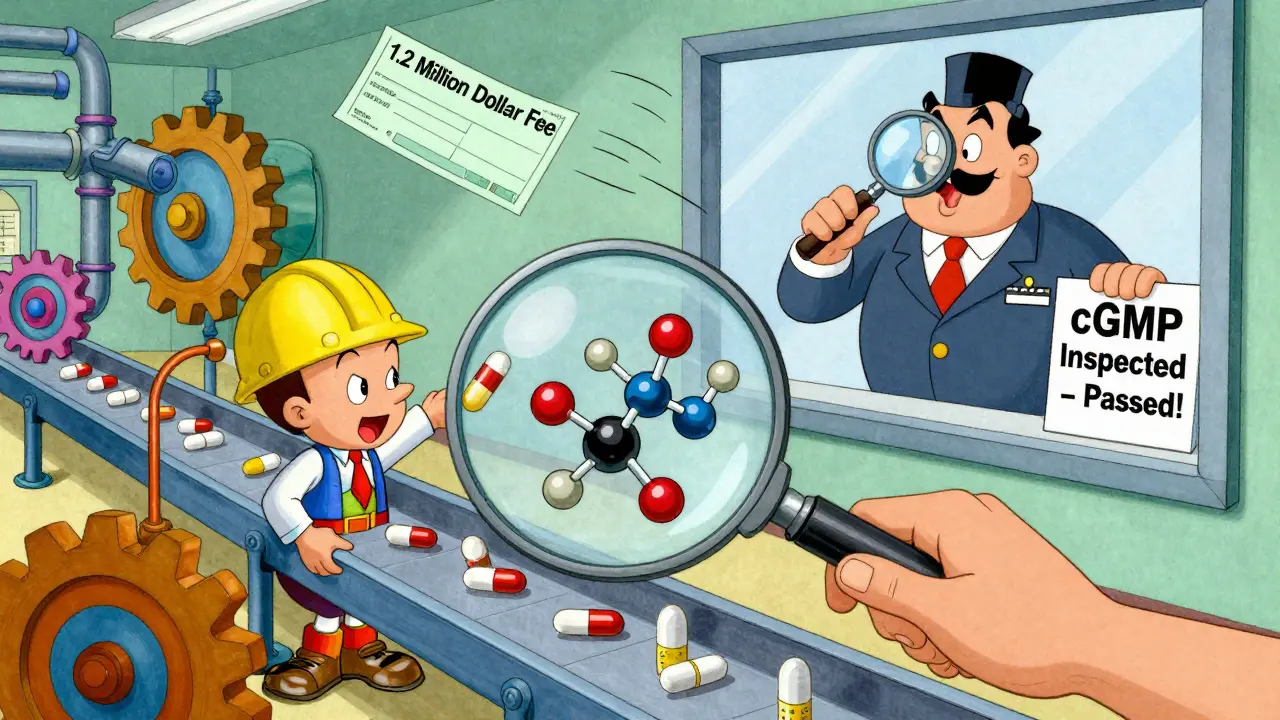

Step 5: Submit and Pay the User Fee

ANDA submissions are paid for under the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA). In 2025, the fee for a standard ANDA is over $1.2 million. This money funds the FDA’s review team. Without it, the process stalls.

Once you submit, the FDA has 60 days to decide if your application is complete. If it’s missing key info, they’ll send a Refuse to Accept (RTA) letter. No review happens until you fix it. Many applicants get RTA letters because of small errors-wrong file names, missing signatures, or outdated forms.

Step 6: FDA Review and Inspection

If your ANDA passes the initial review, it moves into the 10-month clock under GDUFA IV. The FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs assigns a review team: chemists, pharmacologists, statisticians, and labeling experts.

They’ll read every page. They’ll check your stability data. They’ll look at your bioequivalence study design. They’ll compare your labeling word-for-word with the RLD.

At the same time, the FDA inspects your manufacturing site. It doesn’t matter if you’re in the U.S., India, or China. If your facility doesn’t meet cGMP (Current Good Manufacturing Practices), your application is denied. The FDA inspects over 2,000 foreign sites each year. Many rejections come from manufacturing issues-not science.

Step 7: Approval or Complete Response Letter (CRL)

About 75% of ANDAs get approved on the first try. The rest get a Complete Response Letter (CRL). A CRL isn’t a rejection-it’s a list of what’s missing or wrong. Common reasons:

- CMC section lacks stability data for long-term storage

- Bioequivalence study didn’t include enough volunteers

- Labeling doesn’t match the RLD’s boxed warning

- Manufacturing site failed inspection

Responding to a CRL can take 3 to 12 months. Some companies get multiple CRLs. One manufacturer told the FDA’s public forum their nasal spray ANDA got three CRLs over 28 months and cost over $2.3 million in extra testing.

Step 8: Patent Challenges and Exclusivity

If the brand-name drug is still under patent, you can’t launch right away. But you can challenge it. This is called a Paragraph IV certification. You tell the FDA and the brand-name company: "We believe your patent is invalid or we don’t infringe it."

This triggers a 45-day window for the brand to sue you. If they do, the FDA can’t approve your drug for 30 months-or until a court rules in your favor. If you’re the first to file and win, you get 180 days of exclusive marketing rights. That’s worth billions. The first generic version of Humira made over $1.2 billion in those 180 days.

Why This Process Works

Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system $373 billion a year. They make up 90% of prescriptions but only 23% of drug spending. That’s not magic. It’s the result of a system that demands proof-not assumptions.

Some people worry generics aren’t as good. But data shows most are just as safe and effective. A 2019 JAMA study found rare cases where narrow-therapeutic-index drugs (like warfarin or levothyroxine) had minor differences in how patients responded. But those cases were linked to manufacturing inconsistencies, not the ANDA process itself. The FDA has tightened cGMP enforcement since then.

The system isn’t perfect. Review times vary. Some companies get stuck in endless CRL loops. But the FDA is improving. Under GDUFA IV, they’re aiming to review 90% of ANDAs in 10 months and cut median review time to 8 months. They’re also using AI to sort through documents faster.

Bottom line: getting a generic drug approved isn’t easy. But it’s designed to be fair, transparent, and science-based. If you follow the steps, meet the standards, and respect the process, the FDA will approve your drug. And millions of patients will benefit.

How long does it take to get a generic drug approved by the FDA?

The FDA aims to review a complete ANDA within 10 months under GDUFA IV. But the total timeline from start to approval is usually 3 to 4 years. That includes 6 to 9 months for bioequivalence studies, 3 to 6 months for manufacturing development, and 2 to 4 months to prepare the application. If you get a Complete Response Letter, it can add another 6 to 12 months.

Can a generic drug be different from the brand-name version?

Yes, but only in inactive ingredients like dyes, fillers, or preservatives. The active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration must be identical. The FDA requires bioequivalence testing to prove these differences don’t affect how the drug works in the body. If they did, the drug wouldn’t be approved.

Do generic drugs work as well as brand-name drugs?

Yes, for the vast majority of drugs. The FDA requires generics to meet the same strict standards for quality, strength, purity, and stability as brand-name drugs. Studies show that 90% of patients respond the same way to generics as they do to brand-name versions. Rare exceptions occur with drugs that have a narrow therapeutic index, where even small differences in absorption can matter-but these are closely monitored by the FDA.

What is a Complete Response Letter (CRL)?

A Complete Response Letter is the FDA’s official notification that your ANDA cannot be approved in its current form. It lists specific deficiencies-like missing data, flawed studies, or labeling errors. It’s not a rejection. You can fix the issues and resubmit. About 25% of ANDAs receive a CRL on the first review. Many companies get multiple CRLs, especially for complex products.

Why does the FDA inspect manufacturing sites for generic drugs?

Because safety isn’t just about what’s in the pill-it’s about how it’s made. The FDA inspects all manufacturing sites-domestic and foreign-to ensure they follow Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP). If a facility has contamination risks, poor recordkeeping, or inconsistent quality control, the drug could be unsafe. Over 2,000 foreign sites are inspected annually. Many ANDAs are rejected because of facility issues, not science.

What’s the difference between an ANDA and an NDA?

An NDA (New Drug Application) is for brand-name drugs and requires full clinical trials to prove safety and effectiveness. It takes 6 to 7 years and costs over $2 billion. An ANDA is for generics and only needs to prove bioequivalence to an already-approved drug. It takes 3 to 4 years and costs $1 to $5 million. The ANDA skips preclinical and large-scale clinical testing because it relies on the RLD’s existing data.