When seniors experience chronic pain, opioids are often considered - but they’re not a one-size-fits-all solution. Unlike younger adults, older bodies process medications differently. Kidneys slow down. Liver function declines. Fat distribution changes. And with multiple prescriptions already in use, the risk of dangerous interactions skyrockets. The opioids for seniors conversation isn’t about avoiding them entirely - it’s about using them wisely, safely, and only when truly needed.

Why Seniors Need Special Consideration

A 78-year-old with arthritis doesn’t respond to pain medication the same way a 45-year-old does. Their body absorbs, metabolizes, and clears drugs slower. That means a standard dose meant for a younger adult can be too strong, leading to dizziness, confusion, falls, or even breathing problems. The American Geriatrics Society and the CDC both stress that older adults are at higher risk for opioid-related harm - not because opioids are inherently dangerous, but because aging changes how the body handles them.Many seniors take five or more medications daily. Mixing opioids with sleep aids, antidepressants, or even over-the-counter antihistamines can cause dangerous sedation. One study found that over 40% of seniors on opioids were also taking another drug that increased their risk of falls or delirium. That’s why starting low and going slow isn’t just a suggestion - it’s a safety rule.

What Dose Is Safe to Start With?

For someone who has never taken opioids before, the starting dose should be 30% to 50% of what’s typically prescribed for younger adults. That means:- 2.5 mg of oxycodone instead of 5 mg

- 7.5 mg of morphine instead of 15 mg

- Even lower if the patient is frail, over 80, or has kidney or liver issues

Never start with long-acting or patch forms like fentanyl or extended-release oxycodone. These deliver a steady dose over hours, and if the body can’t clear the drug properly, levels build up dangerously. Immediate-release tablets or liquid forms give doctors more control. If a patient needs a tiny dose, liquid formulations are available - no need to split pills, which can lead to inaccurate dosing.

Which Opioids Are Safer for Seniors?

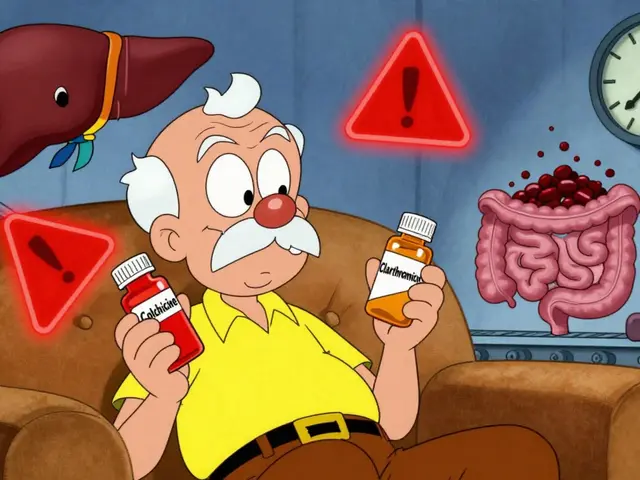

Not all opioids are created equal when it comes to aging bodies. Some should be avoided entirely. Others offer better safety profiles.Avoid these:

- Meperidine (Demerol) - Its metabolite can cause seizures and severe confusion, even at low doses.

- Codeine - It’s converted to morphine in the liver, but many older adults metabolize it unpredictably, leading to either no pain relief or dangerous overdose.

- Methadone - Its long, unpredictable half-life makes dosing risky. Accumulation can cause sudden respiratory depression.

Use with caution:

- Tramadol and tapentadol - These have serotonin-related risks, especially if the patient is also on antidepressants. Can trigger confusion or seizures in older adults.

- Gabapentin and pregabalin - Often used as alternatives, but they cause dizziness, falls, and cognitive blunting in seniors. Studies show they offer minimal pain relief compared to placebo.

Preferred options:

- Oxycodone (immediate release) - Predictable metabolism, widely studied in older adults.

- Morphine (immediate release) - Still a solid choice if dosed carefully.

- Hydromorphone - Useful for patients with kidney issues, as it doesn’t rely heavily on renal clearance.

- Transdermal buprenorphine - A standout option. As a partial opioid agonist, it has a ceiling effect - meaning it doesn’t cause respiratory depression at higher doses. Studies show it causes less constipation and fewer cognitive side effects than full agonists. It’s also safe to use alongside low-dose immediate-release opioids for breakthrough pain.

Non-Opioid Options - And Their Limits

Before reaching for opioids, non-drug and non-opioid treatments should be tried. But don’t assume they’re always safer or more effective.NSAIDs (like ibuprofen or naproxen) - These can cause stomach bleeds, kidney damage, or heart problems in seniors. Use them only for short bursts - no more than one to two weeks - during flare-ups.

Acetaminophen - Safer than NSAIDs, but still risky. The max daily dose for seniors is 3,000 mg. For those over 80 or with liver issues or alcohol use, drop it to 2,000 mg. Many combination pills (like oxycodone/acetaminophen) make it easy to accidentally overdose.

Physical therapy, heat/cold therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy - These are underused but highly effective. A 2023 study showed seniors who combined physical therapy with low-dose opioids reported better function and less reliance on pills than those on opioids alone.

Monitoring Is Non-Negotiable

Starting an opioid is just the beginning. The real work is in watching for problems.Every 1 to 3 months after starting, doctors should check:

- Functional improvement: Can the patient walk farther? Sleep better? Get out of bed without help?

- Side effects: Constipation (almost universal), dizziness, confusion, nausea, or excessive sleepiness.

- Pain levels: Is the pain truly better? Or just masked?

- Risk of misuse: Are pills disappearing? Are they asking for refills early? Any signs of drug-seeking behavior?

Urine drug screens are recommended for anyone on opioids for more than three months. They help confirm the patient is taking what was prescribed and not mixing in other substances.

Also, assess fall risk. Opioids slow reaction time. Combine that with poor vision, weak muscles, or balance issues - and a simple stumble can lead to a hip fracture. A simple timed-up-and-go test can flag high-risk patients.

What About Cancer Pain?

There’s been a dangerous misunderstanding. After the 2016 CDC guidelines, many doctors stopped prescribing opioids to seniors with cancer, fearing overdose. That was a mistake.The 2022 CDC update corrected this. It clearly states: opioids remain the first-line treatment for moderate-to-severe cancer pain in older adults. About 75% of cancer patients respond well to opioids, with half reporting at least a 50% drop in pain intensity. Withholding them because of arbitrary dose limits leaves patients suffering.

The same safety rules apply - start low, go slow, monitor closely - but the goal is different. In cancer care, pain relief and quality of life are the top priorities. If a senior needs 60 MME per day to sleep and eat, that’s not too much. It’s necessary.

How to Talk to Your Doctor

If you or a loved one is considering opioids for pain:- Ask: “Is this the safest option for my body right now?”

- Ask: “What’s the lowest dose I can start with?”

- Ask: “What are the signs I should call you about?”

- Ask: “Are there non-drug options we haven’t tried yet?”

- Bring a full list of all medications - including supplements and OTC drugs.

Don’t accept vague answers like “It’s fine” or “We’ll see how it goes.” Push for a written plan with clear goals: “We’re aiming for a 30% pain reduction and improved mobility within six weeks.” If those goals aren’t met, the treatment plan should change.

What’s Next for Senior Pain Care?

The field is moving toward more personalized care. Pharmacogenetic testing - analyzing genes to predict how someone will respond to a drug - is becoming more accessible. In the future, a simple saliva test might tell a doctor whether a patient will metabolize oxycodone too fast or too slow.Non-drug treatments are also expanding. Targeted nerve blocks, spinal cord stimulators, and virtual reality therapy are showing promise in reducing opioid needs. More clinics are integrating physical therapists and psychologists into pain management teams.

But for now, the best tool remains careful, individualized prescribing - paired with honest conversations and close monitoring.

Can seniors become addicted to opioids for pain?

Addiction is rare in seniors using opioids strictly for pain under medical supervision. More common is physical dependence - meaning the body adapts to the drug - which is not the same as addiction. Addiction involves compulsive use despite harm, which is uncommon in older adults managing chronic pain. The bigger risk is side effects like confusion, falls, or breathing issues - not addiction.

Why is constipation such a big problem with opioids in seniors?

Opioids slow down the digestive system, and older adults already have slower gut motility. Add in dehydration, low fiber intake, and other medications - and constipation becomes almost guaranteed. It’s not just uncomfortable; it can lead to bowel obstruction or hospitalization. Always start a stool softener (like docusate) and a stimulant laxative (like senna) on day one of opioid therapy. Don’t wait for symptoms to appear.

Is buprenorphine really safer than other opioids for seniors?

Yes, for many seniors. Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist, meaning it doesn’t fully activate the brain’s opioid receptors. This gives it a ceiling effect - higher doses don’t cause more respiratory depression. It also causes less constipation and fewer cognitive side effects than full agonists like oxycodone or morphine. Transdermal patches are especially useful because they deliver steady, low doses without daily pills. Studies show it can be safely combined with low-dose immediate-release opioids for breakthrough pain.

Should I stop opioids if my pain gets better?

Yes - but don’t quit cold turkey. Work with your doctor to slowly reduce the dose over weeks or months. Stopping suddenly can cause withdrawal symptoms like nausea, sweating, anxiety, and muscle aches. Even if pain improves, if you’ve been on opioids for more than a few weeks, your body has adapted. Tapering helps avoid discomfort and makes it easier to switch to non-opioid strategies if needed.

What if my doctor refuses to prescribe opioids for my pain?

Ask why. Are they following outdated guidelines? Are they worried about legal risks? Request a referral to a geriatric pain specialist or a palliative care team. Many seniors are undertreated because doctors fear prescribing opioids - but the 2022 CDC guidelines clearly support their use in appropriate cases, especially for cancer or severe arthritis. Your pain matters. Don’t accept being dismissed.

How often should I have my opioid therapy reviewed?

Every 1 to 3 months, especially in the first year. After that, every 6 months if stable. Each visit should include a pain assessment, a review of side effects, a check on functional goals (like walking or sleeping), and a discussion about whether the benefits still outweigh the risks. If you’re not improving, the plan should change - not just the dose.