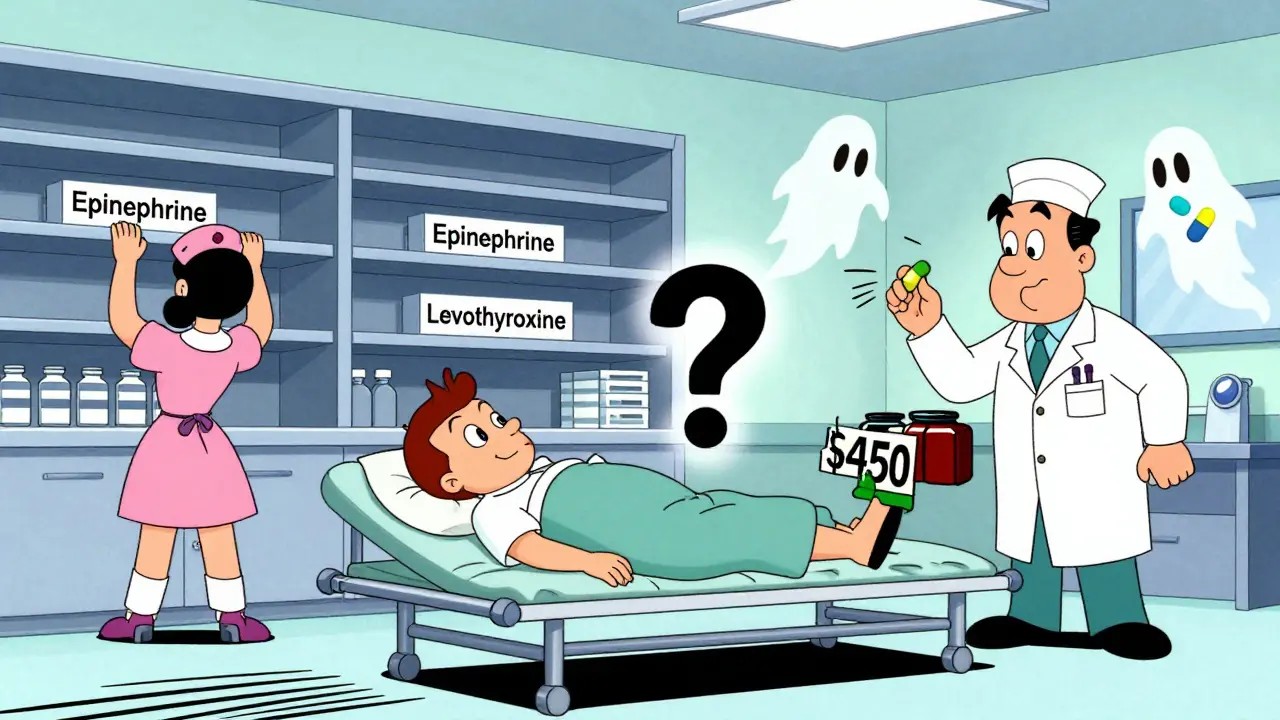

More than 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generic drugs. They’re cheaper, widely available, and trusted - or at least they were. Today, hospitals are scrambling to find basic medications like epinephrine, levothyroxine, and cisplatin. Patients are paying hundreds of dollars more for the branded version. Nurses are switching patients to unfamiliar alternatives. And it’s not random. It’s systemic.

Why the cheapest drugs are the hardest to get

Generic drugs cost less because they copy existing brand-name medications. No expensive clinical trials. No marketing budgets. Just a formula, a factory, and a race to the bottom on price. That’s how the system was designed - and how it broke.The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act made it easier for generics to enter the market. It worked. Too well. Today, a single drug like metformin might have 50 manufacturers competing for contracts. Pharmacy benefit managers and group purchasing organizations (GPOs) pit them against each other, awarding multi-million-dollar deals based on price differences smaller than a penny per pill. When one company drops its price by 0.02 cents, the others have to follow. Soon, no one makes money.

Branded drugs have 70-80% profit margins. Generics? Often 5-15%. Some products barely cover the cost of the bottle. When that happens, manufacturers shut down production. Not because they can’t make the drug - but because they lose money every time they do.

The global factory problem

Most of the active ingredients in your generic pills aren’t made in the U.S. They’re made in India and China. The FDA says 97% of antibiotics, 92% of antivirals, and 83% of the top 100 generic drugs rely on foreign-sourced active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). That’s not a backup plan - it’s the main plan.That creates a fragile chain. In 2020, when India halted exports of acetaminophen and Chinese factories shut down during lockdowns, the U.S. felt it immediately. Fourteen percent of APIs are made in the U.S. today. In 2010, it was 35%. The rest? Overseas. And those overseas factories? Many operate under looser oversight. The FDA inspected 75% of foreign facilities in 2022 - but it only has enough staff to inspect 15% of them annually.

When Intas Pharmaceuticals in India was found with ‘enormous and systematic quality problems’ in 2022, the FDA pulled their cisplatin - a key cancer drug - off the market. No warning. No alternative. Just a sudden gap. Hospitals had to scramble. Patients waited. Some died.

Why modern manufacturing isn’t happening

The solution isn’t just more inspections. It’s better technology. Continuous manufacturing - a process that runs 24/7 with real-time quality checks - is far more reliable than old-school batch production. It reduces errors, cuts waste, and prevents contamination. But it costs $50 million to $200 million to install. For a generic company making pennies per pill, that’s impossible.Branded drugmakers can afford it. They have patents, pricing power, and profit margins. Generics? They’re stuck with 20-year-old equipment. When a machine breaks, they can’t replace it. When a batch fails, they can’t trace it fast enough. That’s why 54% more serious side effects were reported from generics made overseas - not because the drugs are different, but because the systems making them are outdated and unmonitored.

The domino effect of one company quitting

When Akorn Pharmaceuticals shut down in February 2023, it didn’t just disappear. It took 30+ generic drugs with it. Hydrocortisone. Atropine. Phenylephrine. All critical for emergency rooms, ICUs, and pediatric care. No one else could make them fast enough. The market had no redundancy. No backup suppliers. No stockpiles.That’s not an accident. It’s how the system works. With so many players chasing the lowest price, no one invests in spare capacity. No one keeps extra inventory. No one builds extra lines. When one company folds, the drug vanishes. And because generics are so cheap, no one wants to pay to replace them.

Who’s really to blame?

It’s not one villain. It’s a structure that rewards the wrong thing: price over safety, speed over stability, competition over resilience.Group purchasing organizations claim they’re saving hospitals money. But when a hospital can’t get epinephrine for a cardiac arrest, savings don’t matter. The FDA admits it can’t fix this. Its tools are limited to ‘calling manufacturers and asking them to please make more.’ That’s not regulation. That’s a plea.

Some manufacturers say compliance is too expensive. FDA inspections require 5-7 years of documentation. A single Form 483 - a list of violations - can cost $1.7 million to fix and take 18 months. U.S.-based companies have 95% accuracy in records. Some foreign ones? Below 80%. That gap isn’t just paperwork. It’s risk.

What’s being done - and why it’s not enough

There’s talk of tax breaks for U.S. API production. The FDA’s Emerging Technology Program has approved 12 continuous manufacturing lines since 2019. Congress passed the CREATES Act to stop brand-name companies from blocking generic competition. The Biden administration added $80 million for foreign inspections.But $80 million is 12% more than last year - while the number of foreign facilities needing inspection jumped 40%. The 12 new continuous lines? They produce less than 3% of all generic drugs. The rest? Still made on old machines, across oceans, under pressure to cut costs.

Real change would mean paying more for generics. Not a lot - maybe 10-20% more per prescription. But enough so manufacturers can invest in quality, hire skilled workers, maintain equipment, and keep spare capacity. Right now, the system punishes anyone who tries to do the right thing.

What patients and providers are seeing

On Reddit’s r/pharmacy, pharmacists share stories: ‘We’ve switched antibiotics for 17 different infections in six months.’ On Medscape, nurse practitioners write: ‘I had to switch 89 patients off levothyroxine. Each one needs blood tests. Each one is scared.’One Medicare patient saw their monthly heart medication cost jump from $10 to $450 when the generic ran out. Another couldn’t get insulin for weeks. A cancer patient missed a dose of doxorubicin because the batch was delayed. These aren’t rare cases. They’re daily realities.

The FDA’s drug shortage portal saw complaints rise 327% between 2019 and 2022. The most common shortages? Antibiotics, heart meds, thyroid drugs, and cancer treatments. The same drugs that keep people alive.

The future is predictable - unless we change course

Industry analysts predict the number of generic manufacturers serving the U.S. will drop from 127 in 2022 to 89 by 2027. That’s not a forecast. It’s a countdown.Without structural reform - without paying enough to cover real costs - the shortages will keep coming. More recalls. More delays. More patients caught in the middle. The problem isn’t that generics are bad. It’s that the system that makes them is broken.

The next time you pick up a cheap pill, ask: Who made it? Where? Under what conditions? And what happens when they stop?

Because right now, the answer is: nothing. And that’s the most dangerous part of all.