Knowing your genetic risk for cancer isn’t just about fear-it’s about control. If you’ve got a strong family history of breast, ovarian, colorectal, or other cancers, genetic testing can give you real power: the ability to prevent, detect early, or even choose smarter treatments. It’s not science fiction. It’s happening right now in clinics across the UK and beyond, and the science has never been more precise.

What BRCA and Lynch Really Mean

When people talk about inherited cancer risk, two names come up most often: BRCA and Lynch syndrome. These aren’t just buzzwords-they’re specific gene mutations that dramatically change your cancer risk.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are tumor suppressor genes. When they work normally, they help fix damaged DNA. But if you inherit a harmful mutation in one of them, your body loses a key defense. Women with a BRCA1 mutation have up to a 72% chance of developing breast cancer by age 80. For BRCA2, it’s about 69%. Ovarian cancer risk jumps to 44% for BRCA1 and 17% for BRCA2. Compare that to the general population-where breast cancer risk is around 13% and ovarian is less than 2%.

Lynch syndrome, also called hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), is caused by mutations in genes like MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, or EPCAM. These genes help correct mistakes during DNA replication. When they’re broken, errors pile up fast. People with Lynch have a 10% to 80% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer, depending on which gene is affected. Endometrial cancer risk can hit 60% in women. And it doesn’t stop there-Lynch also raises risk for stomach, ovarian, pancreatic, and even urinary tract cancers.

Testing Has Changed-It’s No Longer Just One Gene at a Time

Years ago, if you had a family history of breast cancer, you’d get tested for BRCA1 and BRCA2 only. Today, that’s outdated. Most clinics now use multigene panel testing, which looks at 30 to 80+ genes at once. This approach catches more than just BRCA and Lynch. It finds mutations in genes like PALB2, ATM, CHEK2, and others that also raise cancer risk, but were often missed in the past.

A 2023 study of over 38,000 people found that single-gene testing missed up to half of the actionable genetic findings. That’s a big deal. Someone might test negative for BRCA but carry a harmful PALB2 mutation-something that still calls for extra screening and possibly preventive surgery.

But there’s a trade-off. The more genes you test, the more likely you are to find something unclear-a variant of uncertain significance (VUS). These are genetic changes where we don’t yet know if they cause cancer or are harmless. In the past, VUS rates were around 12-15% for multi-gene panels. That caused a lot of anxiety and confusion.

That’s changing fast. A landmark study published in Nature in February 2025 used CRISPR to test nearly 7,000 BRCA2 variants in the lab. The result? They reclassified 91% of previously uncertain changes in the DNA-binding domain. That means for many people, a VUS is now either clearly harmful or clearly harmless. This isn’t just a lab breakthrough-it’s changing real lives. Around 14,300 people in the U.S. alone are expected to get updated results because of this work.

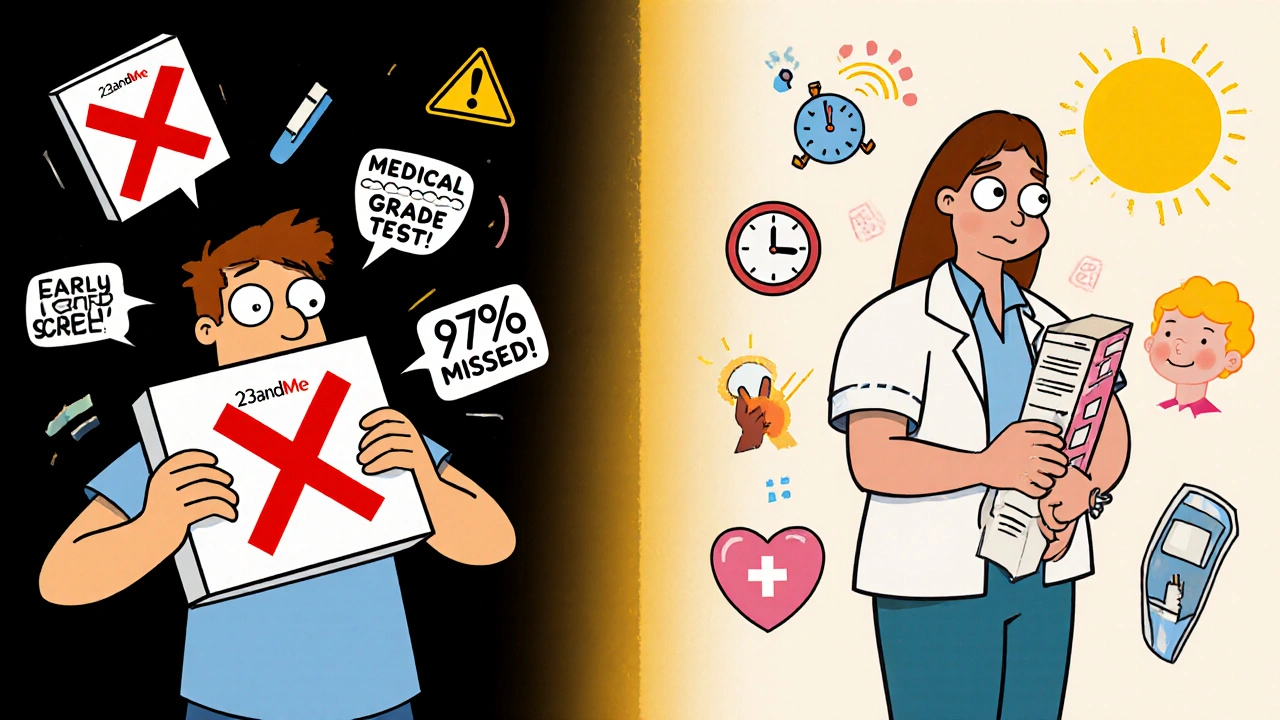

What About Direct-to-Consumer Tests Like 23andMe?

You’ve probably seen ads for at-home genetic tests that say they check for “BRCA mutations.” But here’s the truth: most of them only look for three specific variants that are common in people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. If you’re not from that background, you’re likely getting a false sense of security.

A 2024 study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that 23andMe’s test misses 97% of all harmful BRCA mutations in non-Ashkenazi populations. That’s not a screening tool-it’s a gamble. Relying on it could mean skipping lifesaving medical advice.

Medical-grade testing is done in certified labs, uses blood or saliva samples, and is always paired with genetic counseling. The results are confirmed with a second method (Sanger sequencing) to make sure they’re accurate. And unlike consumer tests, they’re designed to be interpreted by professionals who understand what the data means in context of your personal and family history.

Who Should Get Tested?

Not everyone needs genetic testing. It’s not a routine check-up like cholesterol. But if you meet certain criteria, it’s strongly recommended. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines 2025 say you should consider testing if:

- You were diagnosed with breast cancer before age 50

- You have ovarian, pancreatic, or metastatic prostate cancer at any age

- You have multiple relatives on the same side with breast, ovarian, colorectal, or endometrial cancer

- You have a known BRCA or Lynch mutation in your family

- You’re of Ashkenazi Jewish descent with any personal or family history of breast, ovarian, or pancreatic cancer

And it’s not just for people who’ve had cancer. If you’ve never been diagnosed but have a strong family history, testing can still help you take preventive steps.

What Happens After a Positive Result?

A positive result doesn’t mean you’ll definitely get cancer. It means your risk is much higher-and you have options.

For BRCA carriers, risk-reducing surgeries can cut cancer risk by up to 80%. A 2023 meta-analysis of nearly 13,000 patients showed that removing the breasts (mastectomy) and/or ovaries (oophorectomy) dramatically lowered death rates. Many women report feeling less anxious after surgery-not because they’re cured, but because they’ve taken control.

For Lynch syndrome, the path is different. Instead of surgery, you get frequent colonoscopies-every 1 to 2 years starting in your 20s. Studies show this can reduce colorectal cancer deaths by up to 70%. In some cases, taking aspirin daily has been shown to lower cancer risk too.

And now, for those with Lynch or BRCA mutations who already have cancer, the treatment can be targeted. Immunotherapy drugs like pembrolizumab work exceptionally well in tumors with mismatch repair defects (like Lynch). One 2025 case study at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center showed a complete remission in a patient with advanced colorectal cancer after starting immunotherapy based on their genetic result.

The Hidden Challenges: VUS, Cost, and Access

It’s not all straightforward. Even with progress, problems remain.

First, there’s the cost. In the U.S., a full panel test can cost $250 to $500 out-of-pocket if not covered by insurance. In the UK, testing is available through the NHS if you meet criteria, but wait times can be long. Some private providers offer faster service, but at a price.

Second, there’s insurance discrimination. Even though the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) protects against health insurance and employment discrimination in the U.S., it doesn’t cover life, disability, or long-term care insurance. There have been documented cases of people being denied coverage after a positive result.

Third, access is unequal. A 2025 report showed that Black patients are less than half as likely as white patients to receive genetic testing-even when they meet the same clinical criteria. Reasons include lack of provider awareness, mistrust in the system, and fewer referrals.

And then there’s the VUS problem. Even though rates are dropping, a VUS result can still cause months of stress. One Reddit user in January 2025 wrote: “I got a VUS in BRCA2. My doctor said ‘we don’t know.’ I spent six months terrified. Then I got a second opinion. They reclassified it as benign. I cried.”

What About Genetic Counseling?

You can’t skip this step. Genetic testing isn’t like ordering a DNA kit online. It’s a medical process that requires expert guidance.

Before testing, you meet with a certified genetic counselor. They review your family history, explain what the test can and can’t tell you, and help you decide if it’s right for you. After testing, they interpret the results and help you plan next steps.

The American College of Medical Genetics says genetic counseling is required for interpreting these tests. Yet a 2024 survey found that 63% of community oncologists felt untrained to order or explain them properly. That’s why it’s critical to go to a center with dedicated genetic services-like academic hospitals or specialized cancer clinics.

In the UK, the NHS offers genetic counseling through regional cancer genetics services. In the U.S., organizations like the National Society of Genetic Counselors have a 24/7 hotline that handled over 12,500 inquiries in 2025, with an average response time of 22 minutes.

The Future: Polygenic Risk and Universal Testing

What’s next? Scientists are moving beyond single genes. Researchers at Stanford identified 380 genetic variants that control how genes turn on and off across 13 cancer types. These aren’t single mutations like BRCA-they’re subtle changes that add up. Together, they form something called a polygenic risk score.

In the next 5 to 10 years, we may see tests that combine your BRCA status, Lynch status, and polygenic score into one overall risk picture. That could mean even more personalized screening-like starting mammograms earlier for someone with a high polygenic score, even if they don’t have a BRCA mutation.

And the big question: should everyone be tested? A 2025 ASCO survey showed 67% of oncologists support universal germline testing for all cancer patients. Why? Because finding a mutation changes treatment-and it can save relatives too. But cost and infrastructure are still barriers. Community clinics often can’t afford the staff or systems to manage it.

Still, adoption is growing. In the U.S., 78% of hospitals using Epic’s electronic health record system now have automated genetic testing pathways. That means when a doctor enters a diagnosis of ovarian cancer, the system can automatically suggest genetic testing.

Final Thoughts: Knowledge Is Power-But Only If You Use It

Genetic testing for cancer risk isn’t about predicting the future. It’s about changing it. Whether you’re facing a diagnosis, have a family history, or just want to understand your risk, the tools are here. And they’re better than ever.

But knowledge without action is just information. A positive result means you can start screening earlier, consider prevention, or choose a more effective treatment. A negative result doesn’t mean you’re safe-it just means you don’t have the known inherited mutations. You still need regular screenings based on your family history.

And if you’re unsure where to start? Talk to your doctor. Ask if you meet the criteria for genetic testing. Ask if there’s a genetic counselor you can see. Don’t wait for symptoms. Don’t rely on a DTC test. The science is ready. Now it’s up to you to use it.

Who should consider genetic testing for cancer risk?

You should consider testing if you were diagnosed with breast, ovarian, colorectal, or pancreatic cancer before age 50; have multiple close relatives with these cancers; have a known hereditary cancer mutation in your family; or are of Ashkenazi Jewish descent with any personal or family history of related cancers. Even if you haven’t had cancer, a strong family history may qualify you for testing.

Can I just use a 23andMe test to check for BRCA?

No. 23andMe only tests for three specific BRCA variants common in Ashkenazi Jewish populations. It misses over 97% of harmful BRCA mutations in other groups. Relying on it could give you false reassurance. Medical-grade testing, done in a certified lab with genetic counseling, is the only reliable option.

What does a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) mean?

A VUS means a genetic change was found, but scientists don’t yet know if it increases cancer risk or is harmless. It’s not a positive or negative result-it’s uncertain. Most VUS results are later reclassified as benign after more research. In 2025, a major study reduced BRCA2 VUS rates from 12.7% to 1.1% in key areas, meaning many people are getting clearer answers now.

Does insurance cover genetic testing?

In the U.S., Medicare and most private insurers cover testing if you meet NCCN guidelines, with a 98.7% approval rate. In the UK, the NHS provides testing for eligible individuals based on family history. Out-of-pocket costs range from $250 to $500 if not covered. Some labs offer financial assistance programs.

Can genetic testing help if I already have cancer?

Yes. Finding a hereditary mutation can change your treatment. For example, people with Lynch syndrome or BRCA mutations often respond better to immunotherapy or PARP inhibitors. It can also help your family members get tested and prevent cancer before it starts.

Is genetic testing safe for my privacy?

Medical-grade testing follows strict privacy rules like HIPAA and GINA. Labs use encryption meeting NIST standards. But breaches have happened-over 400,000 people were affected in known cases since 2020. Always use accredited labs and ask how your data is stored and shared. Avoid consumer tests that sell data to third parties.

What if I test negative but still have a strong family history?

A negative result doesn’t mean you’re risk-free. You may still carry a mutation that current tests can’t detect, or your family’s cancer may be due to other genetic or environmental factors. Continue regular screenings based on your family history. Some experts recommend enhanced screening even for negative results in high-risk families.