Chronic Hepatitis B Treatment Effectiveness Calculator

Treatment Efficacy Overview

| Treatment | Functional Cure Rate | HBsAg Reduction | Key Safety |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capsid Assembly Modulator (CAM) | 16% | Significant | ALT flares |

| RNA Interference (RNAi) | 12% | 2.5 log | Injection site reactions |

| Therapeutic Vaccine | 9% | Moderate | Low-grade fever |

| Gene Editing (CRISPR) | Not yet determined | Targeted reduction | Off-target risk |

Key Takeaways

- The goal is shifting from lifelong suppression to a functional cure.

- Capsid assembly modulators, RNAi agents, therapeutic vaccines and gene‑editing tools are in late‑stage trials.

- Combination regimens that pair novel agents with existing nucleos(t)ide analogues show the highest cure rates.

- Safety signals remain manageable, but long‑term monitoring for off‑target effects is essential.

- Clinicians should start preparing workflows for rapid adoption once approvals arrive (expected 2026‑2027).

When talking about chronic hepatitis B, most patients today rely on nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) that keep the virus in check but rarely clear it. Over the past three years a wave of new research has reshaped that reality, moving the field toward what experts call a “functional cure” - loss of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) with sustained viral control without ongoing therapy.

Hepatitis B virus is a partially double‑stranded DNA virus that infects hepatocytes and can integrate its genome into the host DNA, making eradication a tough puzzle. The virus produces several antigens (HBsAg, HBeAg, core antigen) that help it evade the immune system. Understanding these viral components is key to grasp why new drugs target different stages of the viral life‑cycle.

Current Treatment Landscape

First‑line NAs such as tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and entecavir suppress HBV DNA replication with >95% virological response rates. However, they do not eliminate covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) or integrated HBV DNA, meaning most patients stay HBsAg‑positive indefinitely.

Long‑term NA therapy is inexpensive and safe, but it carries a small risk of renal toxicity and bone loss, especially in older patients. The unmet need is clear: a finite therapy that can achieve HBsAg loss.

Emerging Therapeutic Classes

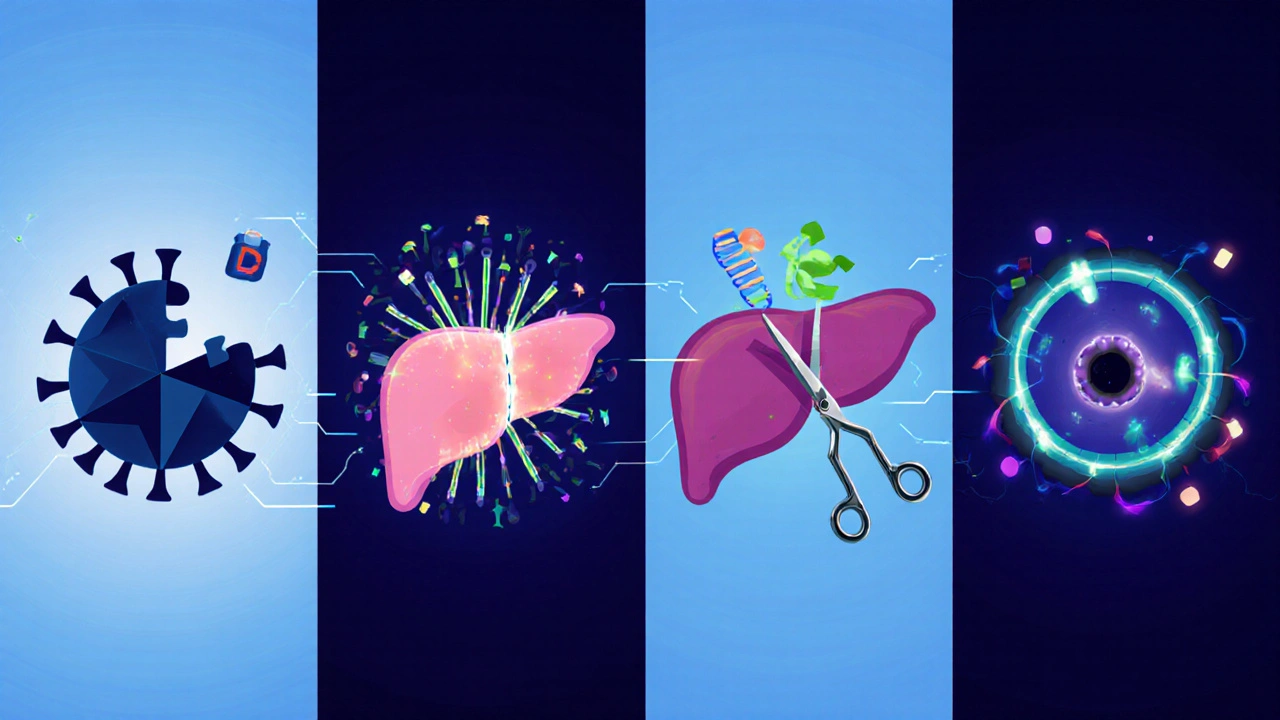

Since 2022, four main groups have entered phaseII/III trials:

- Capsid assembly modulators (CAMs) disrupt the formation of the viral nucleocapsid, blocking both new virion production and replenishment of cccDNA.

- RNA interference (RNAi) therapeutics use small interfering RNAs to silence HBV transcripts, dramatically lowering HBsAg levels.

- Therapeutic vaccines aim to re‑activate HBV‑specific T‑cell responses, helping the immune system clear infected cells.

- CRISPR/Cas9 gene‑editing targets integrated HBV DNA, attempting a permanent genomic cure.

Each class tackles a different viral checkpoint, which is why combination strategies are now the focus of most late‑stage studies.

Clinical Trial Highlights (2023‑2025)

Below is a snapshot of the most promising data that have emerged from the last two years.

| Therapy | Mechanism | Trial Phase | Key Efficacy Endpoints | Safety Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIR‑001 (CAM) | Disrupts capsid assembly | PhaseIII | HBsAg loss in 16% at 48weeks (vs 2% NA alone) | Transient ALT spikes; no renal events |

| ALN‑HBV02 (RNAi) | siRNA‑mediated transcript silencing | PhaseIII | Mean HBsAg reduction≈2.5log; 12% functional cure | Injection‑site reactions; mild flu‑like symptoms |

| HBV‑VAC‑12 (Therapeutic vaccine) | HBsAg‑specific T‑cell activation | PhaseIIb | HBsAg seroconversion in 9% when added to tenofovir | Low‑grade fever in 6% of participants |

| CRISPR‑HBV‑01 | Targeted cleavage of integrated HBV DNA | PhaseI/II | Detectable reduction in intra‑hepatic HBV DNA in 4/6 biopsies | Transient elevation of liver enzymes; no off‑target edits observed on WGS |

When these agents are paired with tenofovir, the additive effect on HBsAg decline is striking. The most compelling signal comes from the VIR‑001 + tenofovir arm, where a functional cure rate above 15% suggests we may finally achieve a finite therapy for a sizable patient subset.

Safety, Monitoring, and Real‑World Considerations

New modalities bring novel safety questions. For CAMs, the main issue is ALT flares that signal immune‑mediated clearance of infected hepatocytes. Clinicians should monitor liver enzymes weekly for the first 12weeks of therapy.

RNAi drugs are delivered subcutaneously every four weeks. Injection‑site reactions are common but rarely severe. Long‑term suppression of HBsAg could unmask occult HBV mutants, so periodic HBV DNA testing remains essential.

Therapeutic vaccines may provoke brief febrile episodes as the immune system re‑engages. No serious autoimmune events have been reported to date, but patients with advanced fibrosis should be evaluated by a hepatologist before enrollment.

CRISPR‑based approaches are still early, and off‑target editing is the primary concern. Ongoing studies employ high‑fidelity Cas9 variants and liver‑targeted lipid nanoparticles to mitigate risk.

Future Outlook: Timeline to Clinical Practice

Regulatory agencies in the US, EU and Asia are reviewing the phaseIII data. If the current trajectory holds, approvals for at least one CAM (VIR‑001) and one RNAi agent (ALN‑HBV02) could arrive by late2026. Therapeutic vaccines are expected to follow in 2027, while gene‑editing remains a 2028‑2029 horizon.

From a practical standpoint, the likely first‑line paradigm will be a short‑course (24‑48weeks) combination of a CAM or RNAi drug with tenofovir, followed by a monitoring period of six months. Patients achieving HBsAg loss will discontinue therapy, entering a “functional cure” surveillance phase with annual HBV DNA checks.

What Clinicians Should Do Now

- Identify patients who are ideal candidates for upcoming trials - e.g., HBeAg‑positive, elevated ALT, and no decompensated cirrhosis.

- Start building hepatitis B registries that capture baseline HBsAg, quantitative HBV DNA, and liver stiffness measurements; this data will be crucial for post‑approval real‑world studies.

- Educate patients about the shift from “lifelong suppression” to “finite cure” and discuss potential enrollment in phaseIII studies.

- Coordinate with pharmacy services to stock subcutaneous RNAi formulations and monitor cold‑chain requirements.

- Stay alert for updated guidance from the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) on combination strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does “functional cure” mean for hepatitis B?

A functional cure is defined by sustained loss of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) with undetectable HBV DNA after stopping all therapy, while the virus may still linger in the liver in a dormant form. Patients remain at very low risk of liver complications and do not need ongoing antivirals.

Are the new drugs safe for people with cirrhosis?

Early data suggest that patients with compensated cirrhosis tolerate CAMs and RNAi agents well, but decompensated disease remains an exclusion criterion in most trials. Until more evidence emerges, clinicians should proceed with caution and consider enrollment in dedicated safety cohorts.

How will combination therapy be administered?

Typical regimens combine a daily oral NA (tenofovir or entecavir) with a weekly or monthly subcutaneous injection of a CAM or RNAi agent. The total treatment course is expected to last 24‑48weeks, after which therapy stops if HBsAg loss is confirmed.

Will insurance cover these upcoming therapies?

Coverage decisions will depend on health‑technology assessments in each country. In the UK, NICE is already reviewing the cost‑effectiveness of CAMs; early cost‑utility models suggest they could be reimbursed if cure rates exceed 15%.

What monitoring is needed after stopping therapy?

Post‑treatment surveillance usually includes HBsAg and HBV DNA testing at 12, 24 and 48weeks, then annually. Liver elastography is advised at 1‑year to ensure no progression of fibrosis.

The landscape of chronic hepatitis B treatment is finally moving beyond “viral suppression forever.” With multiple novel agents showing functional‑cure results in phaseIII trials, patients and clinicians can look forward to finite, potentially curative regimens within the next few years.