If you walk into any endocrinologist’s office on a Monday morning, you’ll hear a lot more than just chatter about A1C and morning sugars. The real buzz? Patients are more informed than ever before, and med options feel endless—especially for type 2 diabetes. Tradjenta (linagliptin) is just one box on the shelf. But why do some doctors nudge people away from it? And what keeps certain meds top of mind for the experts? Let’s zoom out and pick apart the landscape of DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists, so you know what’s really out there—and what professionals are actually recommending when Tradjenta isn’t the best fit.

How DPP-4 Inhibitors Stack Up: It’s More Than Just a Name

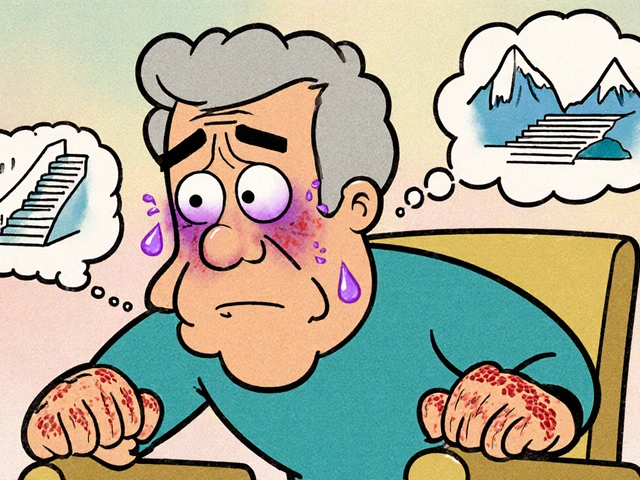

DPP-4 inhibitors (or “gliptins”) get their fame from making the body’s own insulin work more smoothly—without spiking the risk for those nasty hypoglycemic drops. Tradjenta stands shoulder-to-shoulder with a few competitors: sitagliptin (Januvia), saxagliptin (Onglyza), and alogliptin (Nesina). At first glance, these drugs all sound suspiciously alike. They target the same enzyme (DPP-4), extend incretin hormone activity, and help rein in blood sugar after meals. But what ends up mattering are the quirks beneath the label.

Take kidney function, for instance. Linagliptin (Tradjenta) barely needs dose adjustments for renal impairment, making it the easiest pick if kidney problems are on the table. But sitagliptin, saxagliptin, and alogliptin do require some math and caution in those situations. Some endocrinologists really favor Tradjenta for this reason alone even though its glycemic effect might not be significantly greater.

Side effects and interactions might sway the vote, too. Januvia and Tradjenta are less likely to stir up severe allergic reactions or heart failure issues, while Onglyza spooked some doctors after studies hinted at a slightly increased risk of hospitalization for heart failure. This gets real—especially for patients sporting heart stents or anyone with a smattering of cardiac history. Pick your meds like you pick your friends: they should have your back, not make life harder.

Insurance and cost are increasingly huge factors. In the UK, NHS formularies dictate a lot of choices, but private scripts worldwide need to consider shelf price. As patents expire, generic options make some gliptins (like sitagliptin) much gentler on wallets, swinging doctors’ preferences toward them even if clinical effect is basically a toss-up.

Then there’s the nitty gritty: Tradjenta’s once-daily dosing and pill size are friendly for folks who despise handfuls of meds. Meanwhile, sitagliptin wins points for being included in a ton of combo pills—so people juggling multiple drugs can sometimes whittle their routine down to a single tablet a day. Talk about simplifying a morning routine.

So, which do endocrinologists pick when Tradjenta is off the table? Most lean on sitagliptin first for its long track record and broad combinability, especially if the patient has decent kidney function. But in people with advanced kidney disease, linagliptin’s simplified dosing keeps it relevant. Saxagliptin and alogliptin aren’t first-in-line for folks with heart issues, but might work for those without cardiac baggage. It’s not just about glucose—it’s matching the right med to the right body, at the right time.

Curious how these options compare to even more alternatives? For a deep dive, check out this detailed breakdown of alternatives to Tradjenta—there’s a whole world beyond just gliptins.

Why GLP-1 Agonists Are the Talk of Diabetes Clinics

Take a peek at any diabetes seminar lately, and everyone’s buzzing about GLP-1 receptor agonists. These drugs—like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), and dulaglutide (Trulicity)—changed the way doctors attack type 2 diabetes. GLP-1 agonists boost insulin when sugar’s high, keep appetite in check, and even slow down the stomach. But the reason they’re on every expert’s lips? Data show they do more than shave points off blood sugar—they help protect the heart and shrink waistlines at the same time.

Endocrinologists are quick to point out that GLP-1 agonists are especially valuable for anyone juggling diabetes and cardiovascular risks. Folks with a history of heart attack, stroke, or even stubborn high blood pressure can see long-term benefits on these meds that DPP-4 inhibitors can’t touch. Multiple large clinical trials proved semaglutide and liraglutide both cut down on major heart trouble, while linagliptin and the gliptins didn’t stand out in the same way. This isn’t just numbers on a chart—patients actually end up in hospital less, and live longer lives. That sort of result is catnip for diabetes specialists.

But GLP-1 agonists aren’t for everyone. They’re injectables, not pills (though oral semaglutide now exists for those who hate needles—but the absorption can be finicky). Some people can’t stomach them; the most common gripes are nausea, vomiting, and constipation, especially early on. The first few weeks are the roughest. Experts recommend ramping up doses gently, pairing meds with small meals, and staying hydrated to keep queasiness at bay. Over time, most people adjust—but it takes some patience and a bit of lifestyle juggling.

Cost is another sticking point. GLP-1s are often pricier, and not all health plans or NHS formularies approve them for every patient. Some docs resort to creative paperwork or advocate hard for patients with especially high risks, because the right person can see huge benefits. For people with severe kidney problems, certain GLP-1s (like dulaglutide or semaglutide) are actually safer than many DPP-4s, as they don’t worsen kidney function—though side effects may force further discussion.

Experts warn against using GLP-1s in people with a history of medullary thyroid cancer or certain rare kidney disorders, since the data is limited there. But for the majority, the risk-benefit balance leans strongly in favor of newer GLP-1s, especially when weight loss, blood pressure control, and heart health are key goals—not just sugar numbers.

How massive is the weight loss? People on semaglutide (at doses used for weight management) can lose 15-20% of their body weight over a year, on average. That’s a game-changer—and partially explains why “off-label” and “med spa” buzz surrounds these drugs. But endocrinologists still prioritize long-term safety and patient needs, keeping these drugs as serious tools, not just shortcuts for summer bodies.

In day-to-day practice, a common pattern emerges: doctors may start with a DPP-4 for gentler cases or pill-averse patients, but quickly switch to GLP-1s if need for weight loss, heart protection, or extra sugar control becomes obvious. Many guidelines now push GLP-1s earlier in the game—sometimes even before metformin—when cardiovascular risk is in the mix. The old “pills first, shots later” rulebook is out the window. Smart, patient-centered tweaks rule the day.

Real-World Advice and What Patients Ask Their Endocrinologist

When it comes down to it, patients often want more than just numbers—they want to know what life looks like on these meds, what hassles might pop up, and how their choices compare. Here’s where endocrinologists earn their keep: bridging the science with the daily grind.

One massive tip: track side effects honestly during the first month, regardless of whether you’re team DPP-4 or riding the GLP-1 wave. If a med causes new stomach pains, rashes, or headaches, jot it in your phone—or, if you’re analog, write it right on the prescription box. Endocrinologists say clear details help them pivot quickly, before minor annoyances become reasons to quit meds entirely.

People juggling other drugs (like statins, blood pressure pills, or even immunosuppressants) need their pharmacist double-check interactions. While DPP-4s and GLP-1s play fairly nicely with most diabetes meds, there are always exceptions, especially with oddball stuff like transplant meds or certain anti-epileptics. Doctors often loop in pharmacists for an extra set of eyes, especially with complicated combo therapies.

Monitoring is another hot topic. Many folks think “no lows, no worries” with DPP-4s and GLP-1s, but A1C checks every 3-6 months are still the gold standard. At home, random finger-stick checks from time to time—especially after new meals or on sick days—can help spot trends much earlier than waiting for the next clinic visit. Both types of drugs usually avoid severe lows, but nothing’s perfect if dosed too aggressively—especially paired with sulfonylureas or insulin.

Travel trips? Both med classes are friendly—DPP-4s are easy travelers since heat or cold hardly affects them. Most GLP-1 injectables need refrigeration until first use, but then can live at room temperature for weeks. So, packing for a trip to sunny Spain isn’t as tricky as people fear, just toss it in your hand luggage with a chill pack if needed.

If you’re staring at the pile of glucose meds and unsure which way to go, a real conversation with your endocrinologist still beats internet guesswork. They’ll weigh medical history, budget, lifestyle, and even tiny quirks like trouble swallowing big pills or needle fear. There’s no one-size-fits-all pick.

Here’s one last behind-the-scenes nugget from the diabetes trenches: Endocrinologists trade practical success stories as much as they pore over studies. If a patient thrives on a "less glamorous" drug like alogliptin—because it fits their pharmacy and schedule—they’ll flag it for future patients who seem similar. What’s best on paper isn’t always best in practice. And because the diabetes landscape keeps shifting (with next-gen drugs rolling out fast), smart docs stay nimble—always ready to match people with something better if the current plan stops working well.

Trying to weigh up your Tradjenta alternatives? Look for answers not just in charts or listicles, but in the collective wisdom of people who see thousands of cases—and learn a little from every one. That’s how progress really happens.